【投稿步骤及规范】第十五届 “《英语世界》杯” 翻译大赛

时间:2024-07-29 14:59 浏览:次

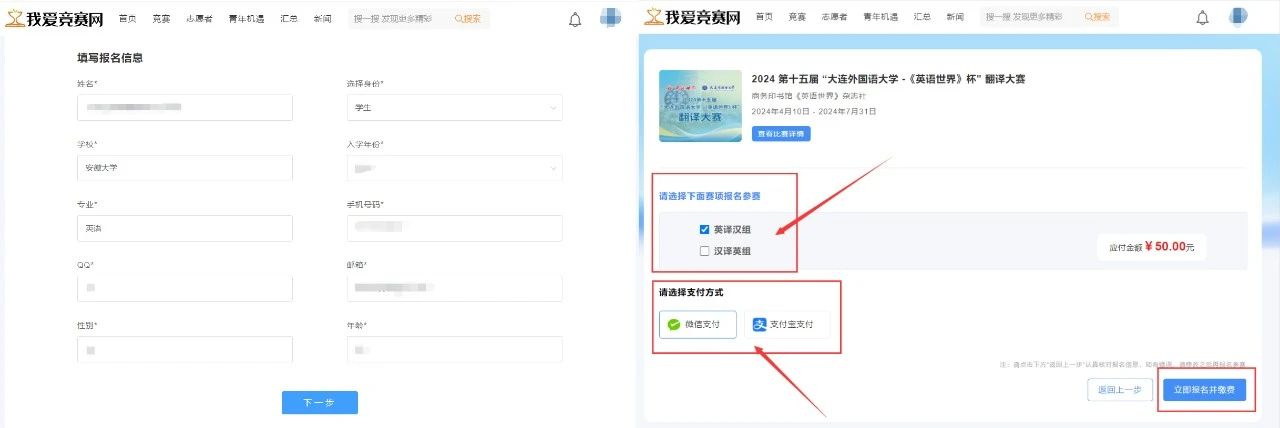

第一步:大赛网站缴费报名 1.使用参赛QQ登录网站:https://s.52jingsai.com/contestsDetail?contestsId=34,登录后点击首页右方【立即报名】  填写完整信息后,点击提交;汉译英或者英译汉可单独报名一个组别,也可同时勾选报名,缴费后即报名成功。

注:报名后没有成功缴费的,所投稿件无法进入评审程序。

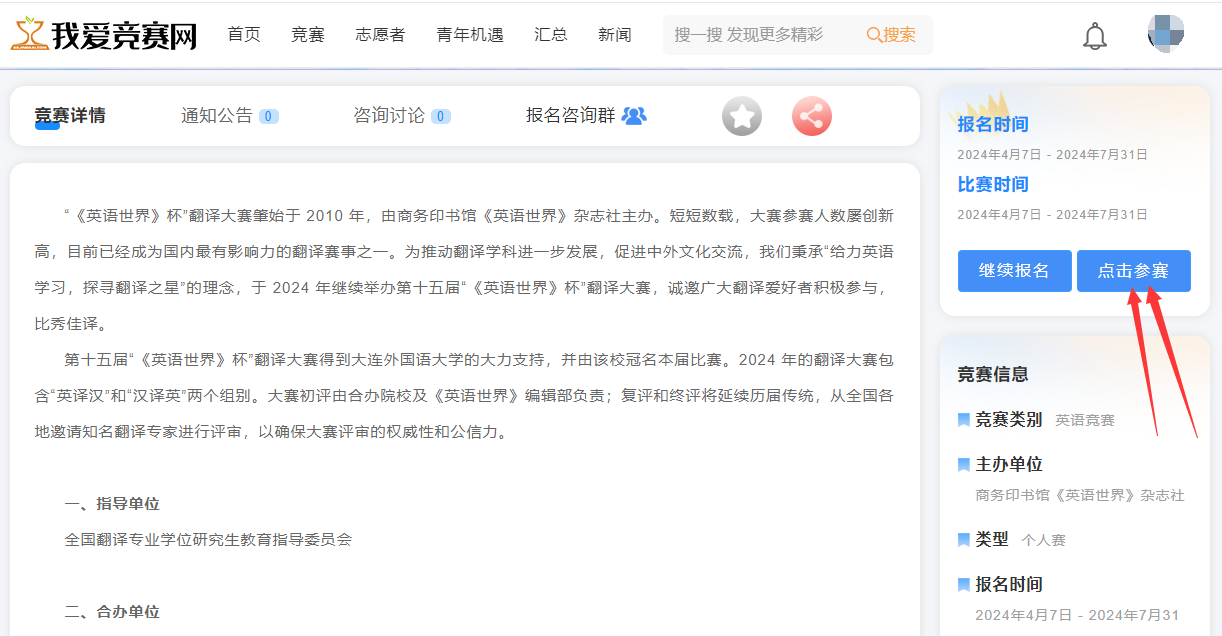

第二步:网站提交译文 1. 大赛报名网站缴费成功后,进入网站首页,点击参赛按钮。

选中大赛及报名的对应组别,并提交;

进入作答页面,将word版(参赛者姓名+报名手机号末4位+英译汉/汉译英)译文上传后提交。  注意: 提交文件中只能包含一版译文,且不能含有任何个人信息,否则匿名评审过程中将被提前淘汰。

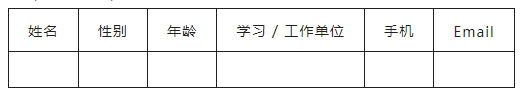

第三步:发送邮件,信息备份 邮件主题:参赛者姓名+个人信息及参赛译文。 邮件内容:人信息表+参赛译文 1. 网站提交成功后,请务必再将个人信息表及参赛译文于截稿日之前以附件形式发送至大赛邮箱:yysjfyds@sina.com。(特别提示:参赛资格确认 及稿件评审以网站提交译文为准,邮箱仅用于参赛者信息及投稿备份。) 2. 个人信息表:文件名“参赛者姓名+报名手机号末4位+个人信息”,Excel 格式,附件发送,项目如下:

3. 参赛译文:文件名“参赛者姓名+报名手机号末4位+英译汉”或“参赛者姓名+报名手机号末4位+汉译英”,Word格式,附件发送;同时参加两项比赛,请发送两个Word附件,请勿合并成一个文件。

译文格式要求: 参赛译文格式:宋体(英译汉)/Times New Roman(汉译英),黑色,小四号,1.5 倍行距,两端对齐。译文每段之前请务必按原文顺序添加编号【1】【2】【3】……(如下方原文所示)。

英译汉原文 What Makes Hemingway Hemingway? —On the psychology of artistic style By Jessica Love 【1】Years after my first and only art history class, I am insufferable at museums. “That’s definitely a Matisse,” I say. “You can tell because of the brushwork and the vibrant use of color.” Sometimes it is not a Matisse. Sometimes it is a Manet, and I am quiet for a while. But usually it is a Matisse, and I am smug as a picnic. 【2】It is unsettling to learn, then, that for all of my carefully won art appreciation, I am in danger of being surpassed by an insect. In a recent study led by the University of Queensland’s Wen Wu, honeybees—whose brains, mind you, are the size of grass seeds—were shown Picassos and Monets paired side by side. Below the prints were two small chambers, one containing sugar water and the other nothing at all. 【3】Which to enter? Bees couldn’t see or smell whether a given chamber held the succulent treat until they’d already flown inside it. But they could let the masterpieces guide them: for some bees, the reward was always under the Picasso, while for the rest it was under the Monet. Over the course of many trials, the bees learned to fly straight for the correct chamber. Indeed, they even performed slightly better than chance when faced with pairs of paintings they’d never seen before. The bees had learned to discriminate, however modestly, between the two artists’ styles. 【4】To be sure, humans still have the edge. Last year a team of researchers at University of British Columbia led by Liane Gabora found that art students were perfectly capable of identifying which well-known artist was behind which obscure painting. Creative writing students were similarly excellent at spotting little-read passages by Hemingway or Dickinson—a skill I can only assume no honeybee has yet demonstrated. 【5】Even more impressively, though, the students could recognize as-yet-unseen samples of each other’s work, including work in entirely different mediums. Creative writers could identify their fellow writers’ paintings and sketches; painters had a pretty good idea who’d brought which poem or clay pot. 【6】It’s clear what the bees were doing: picking up and categorizing complex visual patterns in the pairs of images. But recognizing differences across mediums is altogether different. Whether we’re writing sonnets or building sculptures, Gabora and her colleagues argue, we’re doing so with the same mind: one that structures information in the same way, has been shaped by the same experiences, and yearns to express the same ideas. It should come as no surprise that our techniques and preoccupations in one domain should “out” us in another. 【7】But still I wonder: Just what about these techniques and preoccupations did the trick? The researchers did their best to keep subject matter from ruling the day by instructing, for instance, artists who happened to be surfers not to bring in art that depicted surfing. But what of less obvious subject matter—violent relationships, or Western landscapes? And what of the tics and obsessions that seep into our work unawares? A correlational study like this one, though a fine starting point, will not answer these questions. 【8】Perhaps my biggest question has to do with people who don’t identify as artists, and haven’t settled—or at least would claim so—on a personal style. Are their creations also a reflection of their worldview? It seems likely that, at least to some extent, bad art is all alike, while only good art is good in its own way.

汉译英原文 画龙天下称所翁(节选) 文 / 郑学富 【1】龙的起源与中华人文始祖伏羲有关,龙是中华民族的图腾 , 炎黄子孙是龙的传人,所以龙也成为历代绘画名家的创作题材,三国曹不兴、东晋顾恺之、南北朝张僧繇、唐代吴道子、五代董羽、北宋松所、南宋陈容等。他们都因其出色的技艺和独特的风格而闻名于世,在中国绘画史上具有重要地位和影响力,而唯有陈容被誉为中国古代“画龙第一人”。陈容在继承传统绘画技法的基础上,大胆创新,又有突破,对后世画坛影响深远,元明清三代以水墨画龙的画家大多临摹传承其画法,无出其右者。明代文学家解缙有诗曰:“古来画者谁最工,神妙独有陈所翁。” 【2】龙是古代传说中的神异动物,其形象在典籍中的记载也不尽相同。罗贯中在《三国演义》中借曹操之口描绘得非常生动:“龙能大能小,能升能隐;大则兴云吐雾,小则隐介藏形;升则飞腾于宇宙之间,隐则潜伏于波涛之内。方今春深,龙乘时变化,犹人得志而纵横四海。龙之为物,可比世之英雄。” 画家们在创作过程中吸取古籍中的描述,加上自己丰富的想象,创造出形态各异的龙。在汉唐时期画家笔下的龙多呈兽形 , 宋以后逐渐变为蛇形。《图绘宝鉴》记载,陈容画龙“深得变化之意,泼墨成云,噀水成雾,醉余大叫,脱巾濡墨,信手涂抹,然后以笔成之,或全体,或一臂一首,隐约而不可名状者,曾不经意而得,皆神妙”。南宋诗人刘克庄将陈容所绘的龙与北宋李公麟(字伯时)所绘的马相提并论,称为“伯时马,公储龙”。可见当时陈容名声之显赫。 【3】在陈容的心目中,龙是祥瑞的象征,它遨游苍穹、呼风唤雨,普降甘霖、造福百姓。所以他一生以画龙为己任,赞美龙布雨九土、施恩于民的恩德,以此来抒发自己的鸿鹄之志。 (选自《月读》2024 年第 2 期)

附件1: 附件2: 联系方式: 为办好本届翻译大赛,特成立大赛组委会,负责整个大赛的组织、实施和评审工作。组委会办公室设在《英语世界》编辑部。

参赛QQ群1:225980829(复制群号加群)(已满)

|